VLM Geolocation: Privacy Risks of Vision-Language Models

Visual Place Recognition (VPR) represents one of computer vision’s most practically important challenges: teaching machines to understand where they are by looking around. For robotics and autonomous systems, this capability is vital for navigation and mapping, especially in environments where GPS signals are unreliable or unavailable. But as AI systems become increasingly sophisticated at this task, we’re facing an uncomfortable truth—the same technology that helps robots navigate is becoming dangerously good at invading human privacy.

The Rise of Unintended Geolocators

Vision-Language Models (VLMs) like GPT-4V and LLaMA-3 weren’t specifically designed for geolocation, yet they’re demonstrating remarkable capabilities in this domain. These models can analyze images and infer location information from subtle visual cues that humans might entirely miss—architectural styles, vegetation patterns, street signage, or even the angle of shadows.

The implications are staggering. Millions of users upload images to social platforms daily, often unaware that these seemingly innocent photos might inadvertently expose their private locations, daily routines, or sensitive contexts. With Meta’s integration of LLaMA3-based AI into Facebook feeds, this isn’t a theoretical concern—it’s a pressing reality affecting billions of users.

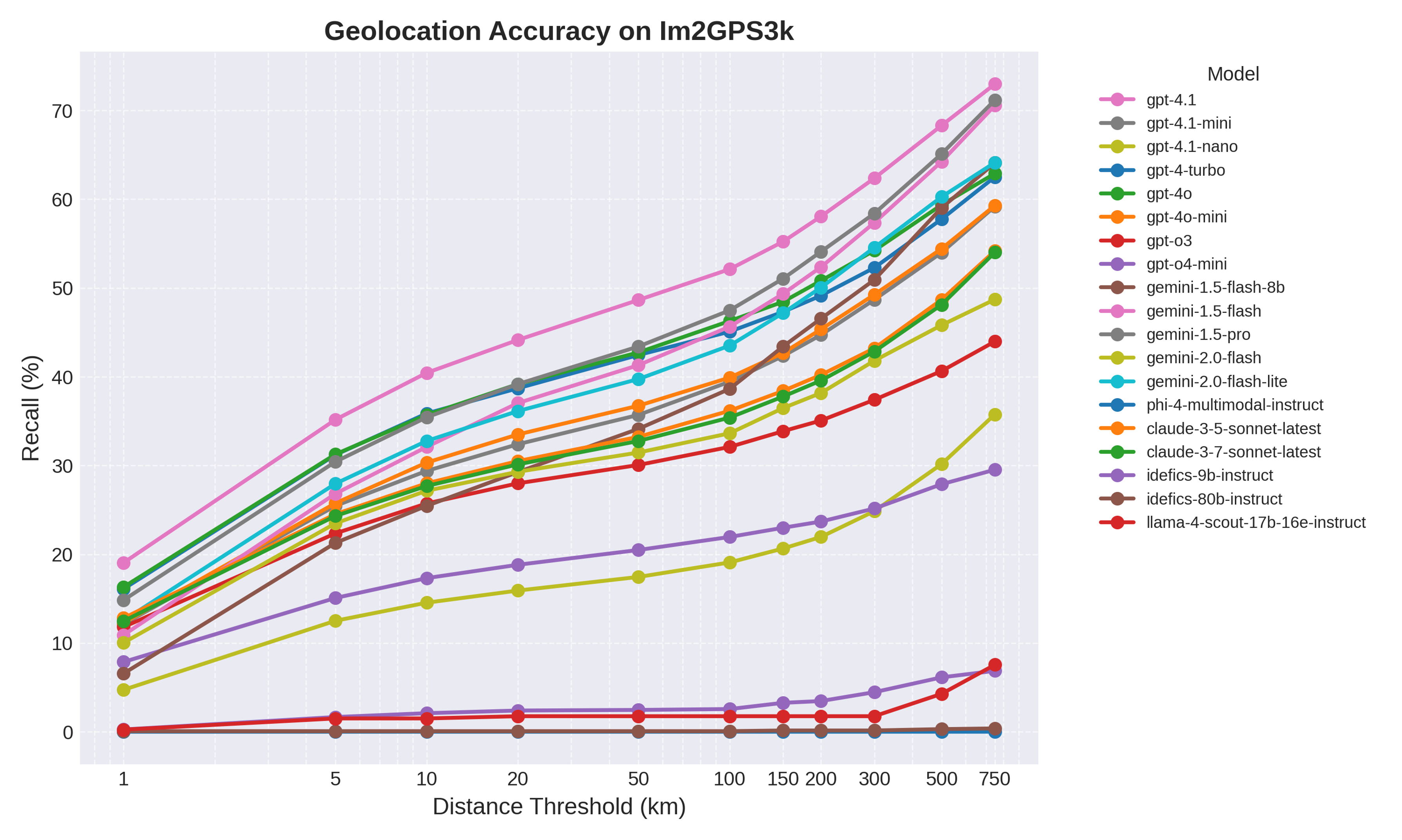

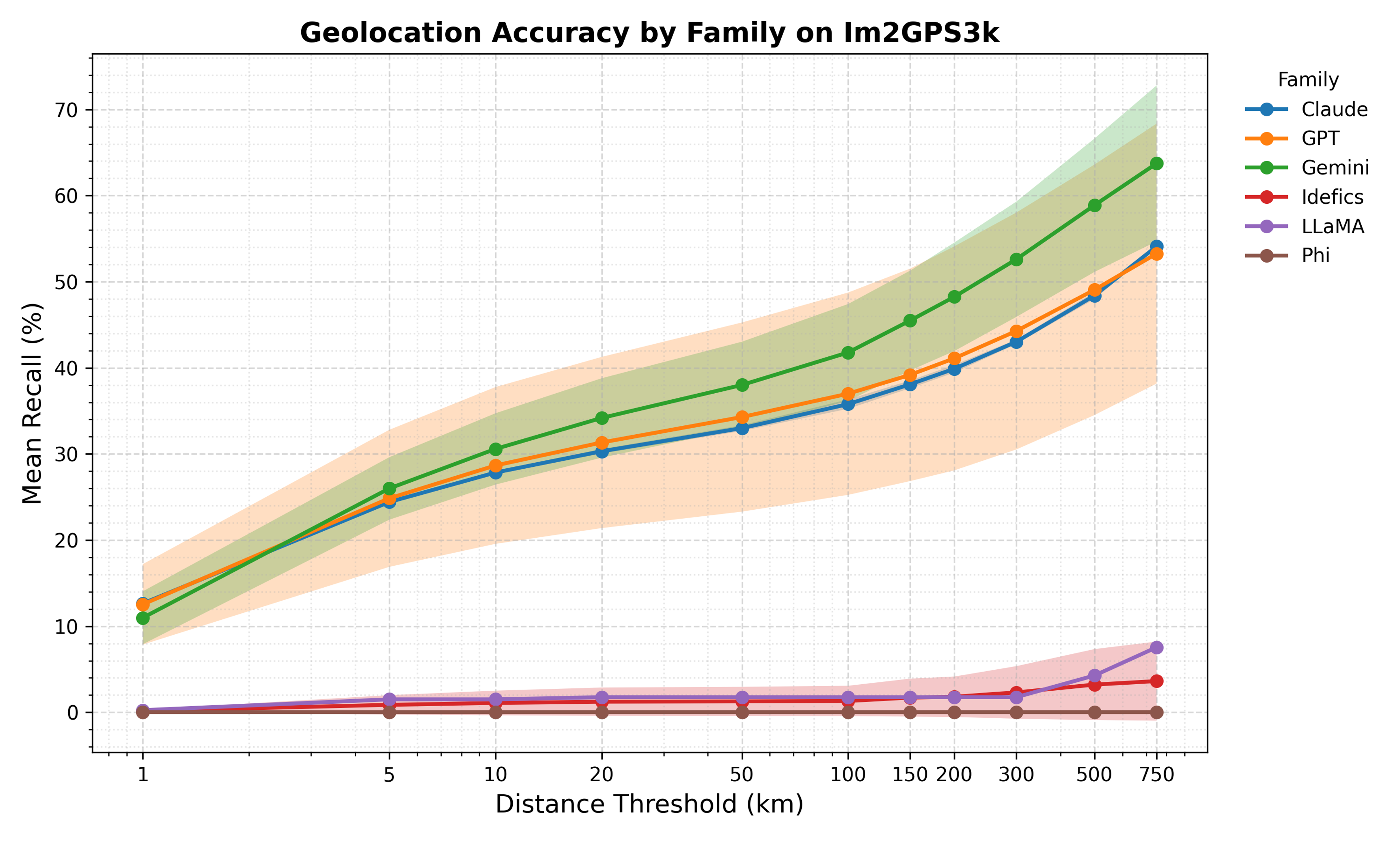

Figure 1: Our systematic evaluation of how Vision-Language Models perform at geolocation tasks across different geographical levels.

Figure 1: Our systematic evaluation of how Vision-Language Models perform at geolocation tasks across different geographical levels.

Understanding the Scale of the Problem

Our preliminary research reveals the concerning precision of current VLMs when tasked with geolocation. We’ve been systematically evaluating these models across multiple geographical scales—from country-level identification down to specific neighborhoods and landmarks. The results show that while these models aren’t perfect, they’re accurate enough to pose significant privacy risks, especially when combined with other available data sources.

The evaluation methodology follows rigorous protocols: we ask models to predict coordinates from input images, compute Haversine distances to ground truth locations, and measure Recall@K performance—the percentage of predictions within K kilometers of the actual location. What we’re finding is that the precision varies dramatically based on the type of location and the visual information available, but the overall trend is clear: these models are getting better, fast.

Figure 2: Accuracy metrics showing how current VLMs perform across different geographical granularities, from country-level down to specific locations.

Figure 2: Accuracy metrics showing how current VLMs perform across different geographical granularities, from country-level down to specific locations.

The Dual-Use Dilemma

This creates what researchers call a “dual-use” technology problem. The same capabilities that enable beneficial applications—disaster response coordination, enhanced navigation systems, geographical education—also create significant risks. Malicious actors could exploit these capabilities for stalking, harassment, or surveillance. Even well-intentioned use cases might inadvertently compromise privacy at scale.

The challenge is particularly acute because the misuse potential scales with the technology’s deployment. As VLMs become embedded in more platforms and applications, the opportunity for both intentional and accidental privacy violations grows exponentially.

Toward Responsible Geolocation AI

This is why our PRIV-LOC project, recently funded by the AI Safety Institute, takes a comprehensive approach to understanding and mitigating these risks. Rather than simply documenting the problem, we’re developing practical solutions that can preserve the beneficial aspects of geolocation AI while minimizing harmful applications.

Our research spans three critical areas:

Technology Assessment: We’re systematically evaluating VLM geolocation capabilities across diverse datasets and scenarios, understanding not just what these models can do, but when and why they succeed or fail. This includes analyzing how different societal groups might be affected, particularly marginalized or vulnerable populations like activists and journalists.

Risk Analysis: Using foresight methodologies, we’re mapping potential scenarios where VLM geolocation might lead to privacy breaches. This includes everything from mass surveillance applications to social engineering attacks that cross-reference social media photos with other personal information.

Mitigation Strategies: We’re developing both technical and policy solutions. On the technical side, this includes methods for introducing controlled noise into geolocation predictions and AI-driven content moderation systems that can flag sensitive images. On the policy side, we’re crafting governance frameworks, transparency requirements, and privacy-preserving mechanisms for platforms deploying these capabilities.

The Path Forward

The future of geolocation AI doesn’t have to be dystopian, but it requires proactive intervention. We need technical solutions that can dial down precision when privacy is at stake, policy frameworks that ensure responsible deployment, and public awareness about the risks these technologies pose.

This isn’t about stopping innovation—it’s about ensuring that innovation serves humanity’s best interests. Visual place recognition will continue to advance, becoming more accurate and ubiquitous. Our responsibility as researchers is to ensure that advancement happens thoughtfully, with privacy and safety built in from the ground up rather than bolted on as an afterthought.

The challenge ahead is significant: balancing the legitimate benefits of geolocation AI with the fundamental human right to privacy. But with collaborative research, stakeholder engagement, and a commitment to responsible innovation, we can navigate this complex landscape successfully.

This research represents ongoing collaboration between the University of Southampton, UCL, and Queensland University of Technology, with support from the AI Safety Institute and industry partners including BAE Systems Digital Intelligence, BT, Flower Labs, and Techfinity Ltd.